This is a fiction inspired by Edgar Degas’ actual five-month sojourn, in the winter of 1872 – 3, with his Creole relatives, in New Orleans. The story emerges over the course of one January day ten years later, when Edgar’s sister-in-law Tell discovers his missing notebook. She is faced with the disturbing truths her gifted cousin could not help seeing, that winter, about her marriage, Edgar, and herself.

“Eloquent . . . inward and poetic . . . haunting. . . . One must slowly savor [Chessman’s] novel, let her determine the temperature, for she understands exactly where the heat must rise and fall.”

— Elizabeth Block, San Francisco Chronicle

“a perceptive book about the artistic expression of perception”

— Historical Novel Society

EXCERPT

So, Edgar, I think to the presence hanging, bruised and grieving, about this new house, this new garden, which – I am all too aware now – contains my history just as surely as it contains these boxes of clothes and shells and embroidered linens. All those paintings you created. All those drawings. Did each one emerge, then, out of some love or sorrow? Some fury or helplessness? Did you hope I would comprehend what was in those images, in spite of not being able to see them with my own eyes? Or did you hope I’d be as unaware of your art as I proved to be?

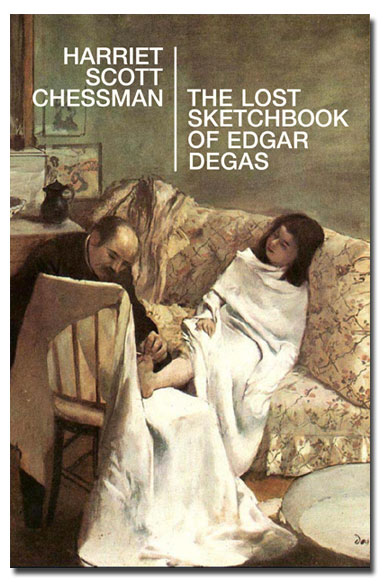

The children awash in the sand and dust of a back garden. The dog with his long pink tongue hanging out, as he does his best to guard the back gate. The gate, ajar, because the husband has already escaped to the house squatting across the ragged fence. The woman blindly arranging flowers, the world around her invisible except for the blur of light green out the window, or not even that. The woman sitting ill at ease in the chair, hemmed in by the table, her hand a claw, her eyes dark pits. The girl wrapped in a shroud-like sheet, on the sofa. The lovely woman sitting cloaked in a chair, pretending to be simply a friend who has been helping in a birth. Two women battling in a saffron room, one pleading in agony, or else rushing to accuse, the other defending herself from accusation, the man a shadow cowering at the piano.

I see it now, how Edgar was indeed holding up a mirror to our life, if only we could look into it with honesty. Easier by far to discount the messenger. Maybe I was a cousin to Eurydice after all, and it was truly Edgar who tried to rescue me. What if I didn’t want to return to the world above, with its blue skies and green grass, if I’d have to see clearly there? In that case, it wasn’t Edgar’s fault. It wasn’t that he looked back, like Orpheus at the threshold. It’s that I turned back myself, happy enough to embrace the blank walls and my dark, disloyal king.